News

Weeks of Continuous Physiological Measurements in a Cetacean Reported for the First Time

Marine mammals rely on blubber as their only insulation from the surrounding environment. Blubber has low conductivity which is preferable in water condition as heat loss is 25 times faster in water than in air at same temperatures. In cetaceans, or whales, the blubber is the main or only barrier for heat loss by reducing conductive heat transfer resulting in lower heat loss in the water. In a current study, the scientists set out to measure the temperature in the muscle-blubber interface and the effects of daily activity on the body temperature. The goal was to try to understand the plasticity of their thermoregulation responses.

Physiological parameters measured for days and weeks

Scientists from the University of Tokyo, Mie University, Teikyo University of Science, Ise Kizuna Animal Hospital and Taiji Whale Museum and Aquarium implanted one 7 year old female Risso dolphin (Grampus griseus) with Star-Oddi’s DST milli-HRT ACT heart rate and activity logger. The logger was implanted in the left axillary space between the muscle and blubber layer. It was set to measure temperature and activity every 15 minutes and heart rate every 30 minutes for 30 days. The logger measured for total of 29 days, of which 11 were used for data analysis.

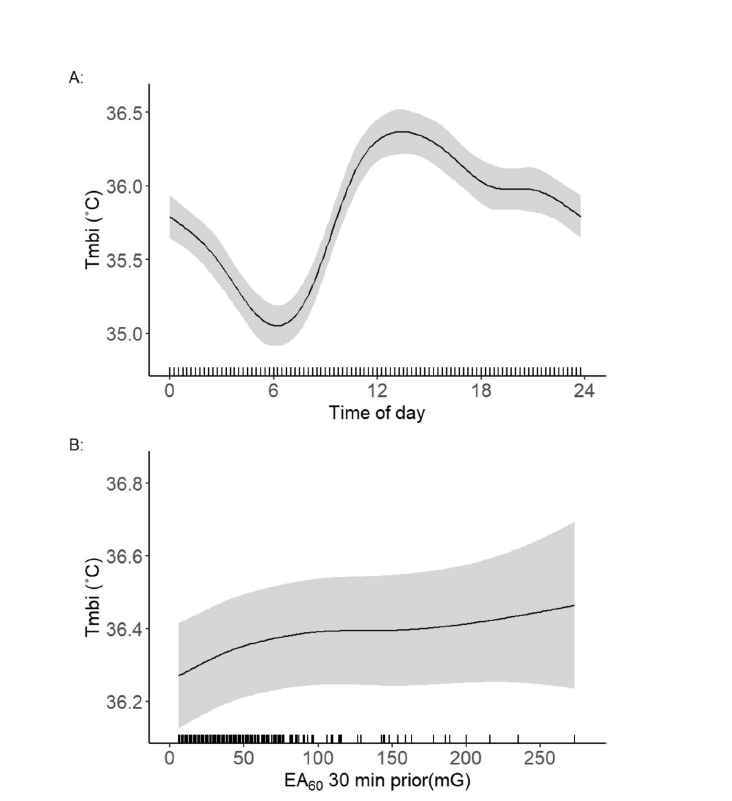

Body temperature (Tmbi) was shown to be diurnal and related to activity

The temperature difference of the muscle-blubber interface (Tmbi) and water (Tw) was found to be on average 13°C. The lowest Tmbi of 34.3°C was found to be in the mornings, and the highest in the daytime or 36.3°C, and 36°C in the evenings. This was shown to have correlation with the level of activity. Tmbi decreased if the activity was lover than 30 mg, and rose with activity over 200 mg, as show in fig. 3 from the article here below.

Heart rate was also found to be diurnal

Variations in heart rate could only be explained by the time of day and showed a diurnal pattern. The heart rate variation could not be explained by activity level nor the water temperature. Furthermore, a sinus arrythmia was detected as well as bradycardia during dives.

To the best of the researcher’s knowledge this study is the first report of weeks of continuous temperature measurements and well as of heart rate for several consecutive days.

Further results can be read in the article published in the journal of Animal Biotelemetry and can be accessed here.